I’ve been asked questions about delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) for years, and lately have received more questions about DOMS than ever, so obviously people are fascinated by this subject and many are concerned about the implications. Some people wonder exactly what causes DOMS, others want to know how to reduce the pain, a few want to know how to avoid it completely and then there are a few “odd ones” who want to know how to get more sore! (Know anyone like that?) In today’s Burn the Fat Blog post, I will answer some of these commonly asked questions about DOMS…

A Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle reader recently asked me this great question about muscle soreness after weight training:

Q: Dear Tom, I’m confused about delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). I’ve read a lot about DOMS. So far, I learned that it occurs especially from eccentric muscle contraction, which is lengthening of the muscle fibers. I also read that DOMS is a type of micro-trauma to the muscle fibers. My question is, what does this say about your training? Does it tell us that our exercise is being properly done in terms of intensity, load, volume and so on, or is it telling us we pushed too hard or we’re over-training and should pull back? In other words, to make a long question short, is DOMS good or bad for you?

Q: Dear Tom, I’m confused about delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). I’ve read a lot about DOMS. So far, I learned that it occurs especially from eccentric muscle contraction, which is lengthening of the muscle fibers. I also read that DOMS is a type of micro-trauma to the muscle fibers. My question is, what does this say about your training? Does it tell us that our exercise is being properly done in terms of intensity, load, volume and so on, or is it telling us we pushed too hard or we’re over-training and should pull back? In other words, to make a long question short, is DOMS good or bad for you?

Out of all the questions I’ve received about DOMS, this question is the most important one: What does DOMS tell us about the effectiveness of our training (and is that good or bad?)

Short answer: DOMS is not a good or bad thing inherently, because it could be a positive or a negative signal. It could be associated with a great workout that stimulated muscle growth, or it could be a sign of over-training or inadequate recovery, not to mention the pain can be debilitating and interfere with subsequent workouts or even activities of daily life (thus, the funny facebook meme photos of people using walkers, wheelchairs and other assisted-movement devices after leg day).

For that reason, I wouldn’t recommend considering DOMS a sign of a good workout or a sign that muscle growth is on the way, only as a sign that muscle damage occurred during your workout.

Now for the long answer, based on all the current science, plus a few opinions of my own, from the perspective of a bodybuilder (aka “meathead”).

Is Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness Good or Bad? A Closer Look…

DOMS is caused by intense exercise, especially resistance training such as weight lifting. It’s true that the eccentric part of a resistance exercise (where you lower the weight and the muscle lengthens) has been linked to greater DOMS compared to concentric movements and isometric contractions (so if you wanted to get more sore, eccentric-emphasis training would be one good way to do it).

Exercise physiologists have known for many years that eccentric muscle actions lead to more DOMS and they also have a pretty good idea why. Overall, eccentric training causes greater muscle fiber and connective tissue disruption and greater release of enzymes associated with muscle damage. Muscles performing eccentric actions also rely more on type II muscle fibers and type II muscle fibers are more susceptible to damage than type I muscles fibers during eccentric actions.

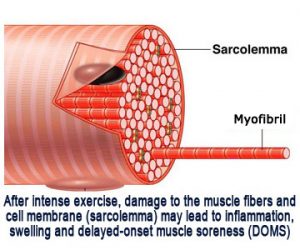

Damage occurs not only to the muscle fibers themselves, but also to the muscle cell membrane, known as the sarcolemma. This is caused by extensive free calcium within muscle fibers. Calcium activates lysomal protease and proteolytic enzymes which damage muscle fiber proteins and structures within the muscle fibers, including the troponin, tropomysin and Z-disks. The actual pain felt as DOMS may not be the muscle fiber damage itself, it may be the edema, swelling and inflammation.

At first, the idea that you are damaging your muscles by weight training and other intense forms of exercise doesn’t sound like a good thing at all. However, breaking down or damaging the muscle structures is actually a part of the muscle growth and strength-building process. You break it down and re-build it, bigger and stronger than before. Feeling soreness after the workout may be an indicator of that breaking down and re-building process.

Brad Schoenfeld, a prominent researcher on the mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy, author of The MAX Muscle plan, and a former competitive bodybuilder says:

“A certain amount of soreness may indirectly benefit muscle development. The response can be likened to the acute inflammatory response to infection. Once the body perceives the damage, immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages and so on) migrate to the damaged tissue in order to remove cellular debris to help maintain the fiber’s ultrastructure. In the process, the body produces signaling molecules called cytokines that activate the release of growth factors involved in muscle development. In this roundabout way, localized inflammation – a source of DOMS – leads to a growth response that in effect, strengthens the ability of muscle tissue to withstand future muscle damage. Adaptation!”

I believe that a moderate amount of DOMS – a soreness in the muscles you last worked that’s noticeable but not debilitating in any way, correlates with a good workout and correlates with muscle growth, provided all the supporting factors are in place for muscle growth to occur. Those include recovery, adequate caloric intake (surplus), adequate protein, the right hormonal environment and so on.

I cautiously emphasize “correlates” with good workouts that produce muscle growth because:

A) You can get sore and not experience growth or strength increase.

B) You can experience growth and strength increase having not been sore.

You might want to read those two points again, and pause to let them sink in if they didn’t click together instantly the first time.

In other words, getting sore after a workout is NOT a prerequisite for seeing muscle growth. Furthermore:

C) You can be so extremely sore that it indicates a degree of muscle damage you cannot recover from, which may mean no growth and decreased strength.

Adaptation and the DOMS Cycle

Soreness is usually the most severe for beginners, but you will probably experience soreness your entire training lifetime, each time you start a new workout program. As your body gets accustomed to one particular workout, the degree of soreness subsides. Whether that’s within a couple of workouts or a couple of weeks, eventually the same workout may no longer get you sore at all (unless you’re intentionally finding ways to introduce new muscular stresses every workout).

You have probably been told by almost every trainer you ever consulted or read, that your body adapts to workouts. Therefore, to keep making progress, you should change your workouts on a regular basis to keep re-stimulating or “shocking” your body. So when you switch to a new workout, lo and behold, you get sore again, and this correlation appears to prove that theory about training adaptation.

The cycle looks like this: Beginner starts training – YEOW! Super sore! —-> soreness subsides after a few workouts —> you change workout program —-> you get sore again —-> the soreness subsides after a few workouts —-> you change your workout program again —-> you get sore again… and so on.

This cycle of getting sore, and no longer getting sore is one of the things that prompts so many questions about DOMS. It naturally makes you wonder if not feeling sore anymore means your workouts are no longer effective. Some people say they never get sore and wonder if they’re doing something wrong. Others are always excruciatingly sore, and they too wonder if they’re doing something wrong. Let’s address these questions.

If You Stopped Getting Sore, Have Your Workouts Stopped Working?

If you ‘re wondering whether your workouts are no longer working if you are no longer sore, the answer is no, not necessarily. If you are still making progress on the same workout (strength is increasing, you’re noticing improvements in body composition, muscle size, etc), your workout is working, isn’t it? If you’re one of those individuals who never seems to get sore, the same principle applies.

That’s why you should not use muscle soreness as your sole indicator of workout effectiveness. The sign of effective workouts is whether you made visible and measurable improvements in muscle growth and strength. Period. In other words, getting sore is not the goal – GETTING RESULTS IS THE GOAL. Was your workout effective? You tell me – did you gain muscle or strength? Do you look better? If so, your workout was effective whether you were sore or not. If someone is bothered by the fact that they are never sore, yet they are making great progress, that infatuation with soreness is purely psychological.

DOMS is more like a side effect of strenuous workouts rather than the goal of a workout. With that said, let me repeat what I said earlier, which is backed up by the science: I believe DOMS does correlate – fairly reliably – with good workouts, at least when the goal is hypertrophy or bodybuilding.

Some trainers disagree that DOMS should be looked at in a positive light. They may dismiss any association with muscle growth as myth or “bro-science” (what “meat head” bodybuilders believe purely from experience). The idea that there is any positive aspect to feeling sore has also been been criticized by strength and conditioning coaches. In that context, their concern has real merit. “You Gotta Play Hurt” may have some truth to it (and makes for a great sports novel), but the fact is, the coach needs his athletes spry and springy every day for practice and frequent workouts and games, and not limping around all week. That makes perfect sense, which is one of the many reasons that athletes generally don’t train like bodybuilders.

Bodybuilders often intentionally set up their programs to maximize muscle damage and microtrauma – they train for higher tension, they control or even exaggerate their eccentrics and they set up training parameters to increase metabolic stress (tension, muscle damage and metabolic stress are known mechanisms for muscle hypertrophy).

Downsides of DOMS And Cautions For Beginners

If this sounds like it’s all upside to the bodybuilder for soreness, it’s not. Extreme soreness can indeed be a sign that you overdid it. This is common with beginners and can be a real de-motivator. In fact, beginners should be aware of DOMS before they start training, otherwise it can be quite a surprise – sometimes unpleasant – and they simply don’t know what to think when it happens. They’re not sure if they’re injured and sometimes even quit, while protesting, “If this is what working out does to you, forget this whole exercise thing!”

Extreme soreness can prevent you from effectively completing your next workout, and if that happens, obviously it’s not a good thing. If you can’t walk up or down the stairs after lower body day or comb your hair after upper body day, you’ve pushed too far, possibly beyond your body’s ability to repair the damaged muscle, and that means no muscle growth. If you’re an athlete and you can’t play the game because you’re “crippled” from the workout you did a day or two earlier, you’ve defeated the whole purpose of training for sports. So get the idea out of your head that extreme DOMS is a good thing. It’s not.

One more thing is good to know about DOMS: Individual responses vary dramatically. DOMS usually begins as early as 8 to 12 hours after training, increases for 24 to 48 hours and peaks 48 to 72 hours afterward, then begins to subside. But studies show that in some individuals, it can last 8 to 10 days! Depending on the severity, eccentric muscle strength can actually decrease during this period.

Some people seem especially prone to excessive muscle soreness (part of your body type/genetics), and there have been cases studied where recovery was not complete for 26 days. In the most extreme scenarios, three percent of individuals may suffer from rhabdomyolysis after an extraordinarily strenuous exercise bout. This is a degeneration of the muscle cells, producing myalgia, muscle tenderness, weakness, swelling and dark-colored urine. In addition to the pain, this causes a loss in the muscle’s ability to produce force.

What’s the Bottom Line?

Light or moderate amounts of DOMS may generally be viewed as a good thing, or at least as a normal thing, especially for the bodybuilder / muscle-size seeker, as long as it doesn’t interfere with subsequent workouts or daily life. And let’s face it, in a “twisted” kind of way, we bodybuilders and serious resistance training people not only don’t mind a little soreness, we kind of like it! It gives us some very immediate feedback that we did something, probably good, and being able to “feel” your muscles in between workouts, I could argue, has some psychological benefits too.

But it should also be clear by now that the goal of your workouts is not to pound yourself into the ground and see how sore you can get. The goal of your workouts is to gain muscle, get stronger and get in shape. If you could achieve that goal without ever feeling sore, for some people, that would be the best outcome of all. For most of us, however, we need to understand what DOMS is and get used to tolerating a little bit or (oddly), enjoying it, whichever the case might be.

Postscript: There is a rumor going around that, “If you don’t like limp-producing muscle soreness, and you like being able to get up and down stairs, don’t train legs with Tom Venuto.” No idea how that one got started…. :-

What do YOU think about DOMS? Do you experience it all the time, often, occasionally, never? Do you like it, hate it or just tolerate it? Post your comments below!

References

Clarkson PM et al, Muscle function after exercise-induced muscle damage and rapid adaptation. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 24: 512-520. 1992.

Ebbeling, CB and Clarkson, PM, exercise-induced muscle damage and adaptation. Sports Medicine 7:207-234, 1989.

Fleck SJ, Kraemer WJ, Designing Resistance Training Programs, Third edition. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, 2004

Frieden J, et al, Myofibrillar damage following intense eccentric exercise in man. International Journal of Sports Medicine 4: 170-176. 1983

Schoenfeld, Brad, The Max Muscle Plan, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL. 2013.

Schoenfeld, Brad, Does exercise-induced muscle damage play a role in skeletal muscle hypertrophy? J Strength Cond Research, 26(5): 1441-1453, 2012. Exercise science Dept, CUNY Lehman College, Bronx, NY.

Talag, TS, Residual muscular soreness as influenced by concentric, eccentric, and static contractions. Research Quarterly 44:458-461, 1973.

Tom Venuto is a natural bodybuilder, fat loss coach, fitness writer and author of Burn The Fat, Feed The Muscle. Tom’s articles are published on hundreds of websites worldwide and he has been featured in Muscle and Fitness, Men’s Fitness, Oprah magazine, The New York Daily News, The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. He has appeared on dozens of podcasts and radio shows including Sirius XM, ESPN-1250, WCBS and Day Break USA. Tom is also the founder and CEO of the premier fat loss support community, the Burn The Fat Inner Circle

Thanks Tom for sharing some great nuggets of wisdom and also research-based information that is easy to understand. I used to be in the camp of working a muscle so hard I would be very sore for several days. But over time, I changed up my workouts so that I’m less sore, but still getting results.

Hey Marc – great to hear from you and thanks for your comment. I used to go for the soreness as “the goal.” now I go for growth and progress as the goal, but I have to say, soreness still often tags along for the ride :-) Cheers, T.V.

I’m now concerned…I try to exercise regularly with this goal in mind: to keep in reasonable shape for my 60+ years of age. Yes, I get at least a little sore most of the time…but I DO NOT want to get muscle-bound or have a body-builder look — I do not want large muscles…they are unsightly for a woman my age, in my opinion. So, based on your article…I should never exercise enough to get sore at all in order to avoid getting large muscles….is that right? Thanks.

No, not to worry. Women do not have enough testosterone to ever be concerned with getting overly large muscles. Its actually VERY VERY hard even for men to get large muscles. it takes months or years of hard work. Weight training is very very important for women age 60 because it is a GREAT way to build bone density and maintain your strength – strength is a very important component of overall fitness. As for the muscle development, in women it shows up as what you would call “tone.” Keep lifting – you’ll be glad you did!

Whenever I work out I stretch between reps and have less soreness. I feel stronger after the stretch as well and do more. For example when hiking or biking I will stop occasionally to stretch and feel more vigor to go longer. I also have fibromyalgia so most of the time my workouts are not as hard as I would like them to be. Thus whenever I do feel muscle soreness I am encouraged that I actually had a workout!

Hi Tom thanks for the article !!!

I noticed when I eat clean consistently

And stay hydrated as well as workout consistently

There is no noticeable soreness but dirty eating and

Dehydration produce weakness and soreness and

Sluggish attitude towards my workouts

Regards

very interesting. If my body is not conditioned to resistance training(took a couple of months off) I will definitely get doms muscle soreness. But after about 2 weeks of training the doms will disappear. I go to a cross-fit gym and no matter how hard the workout, and believe me sometimes i’m in the fetal position at the end of the hour, i always feel fine the next day. when i talk to my fellow crossfitters they always complain about muscle soreness from the last workout. Dumb genetics I guess

Five years ago I was doing a full body workout twice a week. I’d worked up to some fairly heavy lifting for my age and was keeping up with the young guys. A point of pride that I secretly held. I began to feel sore a lot. It was painful to sit and stand and lean over and I attributed it to advancing age. It was like DOMS only never seemed to go away, even after several weeks of workouts that should have reduced the pain to a pleasant reminder that I worked out the day before. I ran across an article about hyper-trophy specific training that reduced sets and reps after a prep period so I cut back to a three day a week gym visit and changed my routine. My soreness was reduced to the normal DOMS after the initial training, and disappeared but for that pleasant reminder of a good workout. I concluded that my constant pain and soreness was a message that I was overtraining and my body protested. So, it wasn’t advancing age. On the other hand, I am older than most of the guys in the gym and I quit trying to keep up with them. DOMS is a message to which lifters should pay close attention.

The most common sense article on DOMS i have read. Really like the line ” getting sore is not the goal – GETTING RESULTS IS THE GOAL”. Well done Tom.

Just make sure you know the difference between DOMS and a potencial debilitating problem looming. For months I had lower back pain and some leg (butt and calf) pain after deadlifts. I assumed it was part of the game as I was lifting heavy. 7 weeks ago my goal was 400 lb lift for 3 reps. After herniating L5-S1 and L4-L5 disks during that lift, my goal now is just to be able to walk 100 feet without pain. If your not sure if the pain you have is normal, ask a certified trainer or physical therapist before its to late. This really, really sucks.

Doug

Thanks for the caution Doug. I would hope that this goes without saying – that people know the difference between ‘it hurts’ and ‘it’s injured’ – but beginners often don’t know whats “normal” and what’s not, and veterans often stubbornly push through “bad pain.” I ruptured my L4 years ago and wouldnt wish it on anyone. Fortunately there is a BIG difference between the pain associated with that kind of INJURY and a little pit of post workout muscle soreness. Cheers, Tom.

PS Heavy deadlifting can be a high risk exercise and despite its extreme popularity right now, the reward to risk ratio puts that one on the do it with caution side – especially for beginners who have not had a coach teach them to do it with proper form.

Thanks for the excellent reply Tom.

I actually have been training about 3-1/2 years to meet this 400 lb deadlift goal. That does (not) make me a seasoned professional but I also didn’t just walk in off the steet and say I was going to lift 400.

Once you get the “Injury” you will definitely know the difference between good and bad pain. OMG will you know! If you listen to your body prior to the injury, “unlike I did”, you will notice the body telling you to back off, especially lower back pain.

As for form on deadlifts, perfect form is paramount. I always started my lift in a rather low squat position and engaged my whole body. About 3 months or so before the accident I was approached by a “trainer” that suggested I raise my rear more prior to lift. It felt strange, but I followed his recommendation.

The point I’m trying to make here is, if you change your form on heavy lifts for any reason, it appears that you should also reduce the weight back down and work up slowly from there. Once you change form, everything is engaged in a new way.

I don’t really expect for you to post this unless you feel it might be beneficial for some of the members. Thanks Tom.

Doug

Thanks Doug for your valuable comment. I should lower the weight first before changing my form.

Hi Tom,

I’ve stumbled upon your website today, and I must say it is quite some good reads here. They are very sensible and have some great information. Thanks for sharing good info! I’ve only been training for about a year, started exercising about 2 and a half years ago, but didn’t start lifting until earlier this year. I’ve recently switched trainers, and even though I have always been quite confident in my leg strength, I am currently experiencing the craziest DOMS I’ve ever had, even compared to when I first started training and lifting. Thanks to the article though, I’m a bit more comfortable with it and I know I’ll survive. lol I’m just curious – do a lot of other people – even with people who have been training or have trained for a while – will doing more reps/different combination of similar workout trigger more intense DOMS just because it is different from the body is used to, even though they are essentially the same movements as before? Please let me know and keep up the great job of the articles! Thank you.

Hi sophie. some people are simply more susceptible to it than others. But i can say that these things will trigger it more in most anyone: 1. a lot of negative emphasis training, 2. doing new workouts youve never done before or first time in a long time (new stimulus youre body is not used to = more soreness), 3. high volume bodybuilding style training with high intensity and lower frequency, ie, working each muscle only once a week or once every 6 days, usually produces more soreness as well

Whenever I start a new weight based exercise program I get intense DOMS. If I stop exercising for over two weeks it returns also – it’s a great motivator not to stop lifting. What I’m wondering though is if the program is intense, and I don’t mean insane, just intense and it’s a new for my body I always get full body flu like symptoms. It’s really horrible and has had me in bed for 24 hours (it starts 24 hours post exercise and peaks at 48) unable to do anything. I’m pretty sure I have some rhabdo going on from urine changes but what id love to know is if this is safe? It’s not something that’s easy to temper because it happens whenever I take a holiday and to give you an idea of ‘intense’ it’s absolutely nothing out of the ordinary, just a workout where if go to failure.

So glad to have found you and my other half is buying your book now. It’s great :). Thanks

Rhabdo is not something you want (despite crossfit jokes and tshirts to the contrary), and it is not normal at all get horrible flu like symptoms every time after training. You may in fact be one of those individuals who is hyper-sensitive and gets sore very easily in general but anything you do in the gym that knocks you out of the gym so you cant train at all, from a practical standpoint alone (let alone whatever it is medically), that obviously does not behoove you. It would be wise to explore different training methods of different intensities and watch carefully the response in your body, also look into all the recovery-enhancement methods, try them and see what helps (ranging from cool down, active recovery, self massage, massage, plus the usual lifestyle stuff and on from there), and one last thought: high volume infrequent training programs like the bodybuilding workouts i do tend to break down a lot of tissue and produce a lot of soreness that keeps coming back – if you dont train a muscle group again for 5-7 days… a 2X per week or even 3X per week frequency with much less volume may condition your body to adapt quickly and soreness should not only be less due to the lower volume, but your body may adapt in a way that within a week or two, youre not getting sore like you would be doing 1 muscle group a week with high volume. if all else fails, go check with a medical professional because again, “horrible” and “in bed 24 hours” is not what youre supposed to feel like after routine training

I am actually puzzled by own body’s reactions because I am not a newbie to weight lifting (been doing it for about 2 years) but am sore ALL THE TIME – I get conflicting advice…If I rest 2 or even 3 days, I’m still sore but go back to exercising. Not sure why my body never gets accustomed to my routine and I’m always sore???

partly genetics – some people just get more sore. Partly recovery: proper program design., lifestyle, nutrition etc. Partly style of training. Bodybuilding styles of training with high volume and longer time between working each muscle = more sorness than lower volume more frequent training, slow negatives (eccentrics) = more soreness and so on. 2 out of 3 of those things you can control. 1 you cant. So you may be able to improve recovery and alter training style to reduce soreness, but if soreness is not debilitating, its really ok and is just par for the course.