In part two of Tom Venuto’s interview about his trek on the Pacific Crest Trail, he talks about what kind of nutrition plan fuels 20 to 30 miles a day of hiking, how does body composition and body weight change from burning 5000 to 6000 calories a day, how should you train to get in hiking shape before a long distance trek, what do you learn about the human body from hiking a 2650 mile scenic trail, what was the most difficult challenge on the trail, and much more… [back to part 1]

Let’s talk for a minute about nutrition. What was your plan going in and how did that plan morph over time, and did you surprise yourself, or have any attitude changes along the way?

I knew I would be burning about 5000 to 6000 calories a day maybe more if it was a big day like 30 miles or if there was a pass to go over and it was a 5000 foot elevation gain, and I found out that it’s not practical to eat that much or even carry that much because your food is weight and the more weight you carry, the slower you go, the harder it feels, the more uncomfortable it is and the higher your chance of injury.

I knew I would be burning about 5000 to 6000 calories a day maybe more if it was a big day like 30 miles or if there was a pass to go over and it was a 5000 foot elevation gain, and I found out that it’s not practical to eat that much or even carry that much because your food is weight and the more weight you carry, the slower you go, the harder it feels, the more uncomfortable it is and the higher your chance of injury.

So my plan was I accepted that every full day on the trail, I’d be running a calorie deficit, and I just wanted to keep the deficit small. I planned to eat 4000 to 4500 calories a day, and I was pretty good at hitting those numbers – it was a lot of food, but it was still a deficit.

I also planned to eat most of my calories from healthy food not too far from what I usually eat. I usually eat 90-95% of my calories from nutrient-dense foods. That’s not very realistic on the trail but I figured as long as I ate the majority of my calories from healthy food, after that, anything goes to hit the calorie intake I needed. I think about 70% of my food was healthy and 30% of my calories was anything goes.

The other thing I did was to go stoveless to save weight and trouble. It didn’t bother me – I didn’t mind not having hot meals – I got them in town in restaurants.

A typical day meal plan started with oatmeal, vanilla whey protein and raisins for breakfast– sometimes twice. I liked it – that was my favorite meal and it’s exactly what I usually have every morning except at home I’ll have the oatmeal hot and use fresh fruit.

A whole wheat or whole grain tortilla with peanut butter was also a regular meal. I had a trail recipe I called it the Tortuga tortilla – I’d chop up a chocolate protein bar and roll it up in the tortilla with the peanut butter. I would eat peanut butter right out of the jar too.

I would also eat almost every day instant rice, the kind that’s pre-cooked. And what I did since I was stoveless, is I used an empty peanut butter container as a re-hydration jar. I’d put the rice in there, add water and in about an hour or so, the rice absorbed the water and was ready to eat.

I tried to eat protein with most of my meals. I liked the flavored tunas and two packets would give me 28-36g protein, so I’d have that with my rice. Sometimes I’d go with salmon packets instead.

I normally eat whole baked potatoes and sweet potatoes at home, but that’s not going to work on the trail, so I ate Idahoan mashed potatoes through the whole hike – that’s classic hiker food, everyone was eating those and you could find them just about everywhere. They’re loaded with preservatives so I wouldn’t eat that except on a hike, but I found them palatable, even cold soaked.

And then I ate a lot of high calorie snacks between meals, usually trail mix and nuts and lots of bars. Pro bars have about 400 calories and they’re really popular with hikers. I’d eat one of those along with one protein bar as a snack. And I’d eat whatever bars I could find in the stores – Cliff bars, Kind bars, Power bars; bars and more bars.

Sometimes it depended on what was available at the little stores. At some of these small country stores in small towns, I had to take whatever was on the shelf. Once in a while I had some beef jerky or Ramen noodles, which is another thru hiker staple. But I was pretty consistent and ate mostly the same every day which I think helped me manage my calorie intake and my weight a lot better than if I were eating at random.

Idahoan mashed potatoes and Ramen noodles… not my usual fare, but staples on the trail

Were there foods you got so sick of that you can’t eat them ever again?

I don’t think, unless I was back on the trail again, I could eat more bars or trail mix. Even nuts. I like nuts, and I’m sure I’ll eat them again, but it’s going to be a while. I like potatoes and eat them almost every day, but I only ate the Idahoan powdered mashed potatoes because they’re dehydrated, light, and convenient for the trail. Not eating those again. You definitely get sick of certain foods.

If you don’t mind sharing, how did your body composition change, from the beginning to the end, and how did that differ from your expectations?

Well my expectation was that I was going to lose weight. I just wanted to keep it to a minimum and not end up looking like an anorexic. If I lost 10 pounds no biggie; lose 15 and I’d be skinny, but I could deal with it. Lose 30 pounds? No way, I didn’t want that to happen and it does happen to thru hikers. I was even talking with a thru hiker who was ahead of me on the trail and he had lost 40 pounds before I even started. And if you start a hike already lean, that means a lot of the weight loss is probably going to be muscle.

The funny thing is I actually lost weight before I even started. I weighed 195 pounds before training for the hike – because I was doing serious heavy lifting and was pretty bulked up – that’s a heavy body weight for me, not super lean.

Then I started doing training hikes out here on the East coast on the Appalachian Trail and in Harriman State Park to get in shape for the PCT, and I built up to 26 miles in one day and I did so much hiking before starting the PCT, my weight dropped down to 183 without even trying and that’s what I weighed at the Mexican border when I started.

The trails of Harriman State Park, and the Appalachian Trail were great training grounds to prep for the PCT (This is way out in the woods, but you can see Manhattan from here)

I was a little worried that already having lost 12 pounds, what would happen on the trail – would I drop to 160, 150? Would I look like a POW starvation victim?

Well the fourth day on the trail I went into a little town in the San Diego backcountry called Julian. I went to the gym there to lift and I weighed myself and I was already 179 – down 4 pounds in 4 days. I was a little panicked because I was thinking, a pound a day? That’s too fast! What if I keep dropping weight at this pace?

What I found out was that after hiking in the desert, I would show up in town dehydrated, but after filling up with fluids and eating some big meals with sodium, my weight would usually pop back up. Sometimes there was a net weight loss, but I realized my weight was going to fluctuate especially in the desert with the heat.

So what I did to make sure the net weight loss was small was to eat until I was stuffed in town – and it was great at first, but to be honest, the novelty wore off quick and it was hard to keep eating enough. But it worked and I was able to hold my body weight in the upper 170s for the first 700 miles and I had good access to gyms in Southern California so every time I went into town to resupply, I went to the gym.

For a “meathead” hiker, a visit to town meant two priorities: Lift and eat! (Pictured: Reps Gym, Mountain Center California, near Idyllwild, and a typical “hiker breakfast”)

Then I reached the Sierra around mile 700 and that’s when it got really tough. The Sierra mountains were so physically demanding, when I got out the other side I looked in the mirror when I was in town, and all the abs were in, veins, pretty ripped, but I had lost a lot of size – especially my legs but even my arms looked skinnier than they ever had in my whole adult life. If I had to guess I’d bet I dropped into the upper 160s – but I don’t know because I didn’t have a scale.

What I did was I just kept eating and I kept lifting when I was in a town that had a gym and I would eat as much as I could in town. When I weighed myself in South Lake Tahoe I was holding at 172 pounds.

The only time after that it got really hard to maintain my weight was when I got to Northern California. The terrain is more flat, so you can hike more and I was building up to 30 miles a day, but then I started dropping weight like crazy again. I don’t know what would have happened if I had kept up that pace into Oregon, but I hit the fires and had time to rest when I was skipping around fires in between towns, so my weight stabilized there.

Overall, I stuck with my plan and it worked. My weight and body fat fluctuated a lot – mainly it always wanted to drop, and then I would eat a lot and it would come back up, and then it would drop again, but I kept fighting it, and basically I had a deficit on the trail and a surplus in town, and that helped me maintain my weight more or less.

Eating surplus calories in town is a tough job, but someone has to do it… Mushroom cheeseburger with sweet potato fries in Lake Tahoe

So it wasn’t as bad as you thought?

Right, it wasn’t as bad as I thought. I had to eat a lot, to the point that honestly it was uncomfortable. Everybody jokes around about how great it is that on a thru hike you can eat anything you want and as much as you want and you’ll never gain weight, and that’s more or less true, but for me that was one of the difficult things about the trail, to eat enough not to lose a lot of weight.

You were very fit when you started. Did this differ a lot from others on the trail, and did it give you an advantage? Or would it have been better to have started with, for example, a higher body fat percentage?

With other people I met on the trail that I talked to, there was a mix of people who trained before or were already seasoned hikers, and there were people who didn’t train at all or had never hiked before, it was just a bucket list item to do the PCT. I think it’s hard to disagree that the best way to get in shape for backpacking is backpacking. So there is a theory about how to approach a thru hike and that is to get in shape on the trail.

Basically someone would argue, why bother training before the hike, especially if you’re busy with a full-time job – how are you going to have time for long training hikes when you’re working all day – so why not just train on the trail? You could start with 5 or 6 miles your first day. Then build up to 8-10. Then 12-15 and then eventually within a few weeks on trail, you’ll be doing 20 and then hitting 25, and by the time you’re in Northern California you’ll be doing 30 like everybody else.

That makes sense and I guess there’s some merit to that approach. But that’s not what I did. I trained to get in shape before the PCT by backpacking on trails out on the east coast, and I think it was an advantage for a few reasons. First of all, I was in shape to do 20 miles a day right from day one on the PCT.

But more important I think, is training before the thru hike prevented me from getting injured or at least from, shall we say, unnecessary suffering. Lots of people drop out from injury early on because they’re not trail–ready, and they build up their mileage too quick. Plus they’re not used to the terrain, their shoes, their pack, so they get foot problems, blisters, muscle strains, terrible muscle soreness, or real injury. I think that’s an advantage of training before starting your thru hike.

I also think it’s an advantage because it gives you a chance to test out your gear and shakedown your pack. You might find out you’re carrying stuff you don’t need, or you may find you had the wrong shoes, or your pack doesn’t fit right, or you don’t like your tent and dozen other things.

I arrived here at the Mexican border (Southern terminus of the PCT), already in shape and ready to do 20 miles a day

As a far as would it be better to start with more body weight or body fat percentage, I’ve heard those discussions where some hikers wondered if they should eat like crazy before the hike to gain some weight, and this way if they lose a lot of weight on the trail, it’s not as big a deal. It seems logical but I don’t completely agree with it.

Most thru hikers are obsessive about getting their pack weight down – they’ll buy all kinds expensive ultralight equipment made from high tech material that weighs next to nothing, because the more you can get your pack weight down, the less weight you have to carry, the more miles you can hike and the more you reduce risk of injury and the easier it’s going to feel. The heavier your pack is, the more you’re suffering but it’s something you could reduce.

But if it’s good to lighten your pack, what about your own body weight? I figure that any excess fat you’re carrying is unnecessary weight – and there’s a correlation between lower body weight and higher mileage and between high body weight and injury. So as far as getting in shape before a hike, I think it makes more sense to lose excess fat beforehand especially if you have a lot of it, or at least don’t go out of your way to gain weight, then you just have to try to maintain energy balance as much as you can on the trail.

Hiking through the high sierra is easier when your pack is light… and you are light!

That makes sense. So did you learn anything new about your body or about other people’s bodies, through observation, over the long months of the hike?

The main thing is that you’re stronger and have more endurance than you think. You can do a lot more than you give yourself credit for. I think I would describe it as I learned you have a second wind. The only catch is that it doesn’t kick in until you hit the wall where you feel like you can’t go any further, then make the effort to keep going through it, and you get to the other side and all of a sudden it gets easier and you can keep going.

I also learned that you can handle a lot more pain and discomfort than you think, you just need to learn the difference between hurt and injured. If you’re injured and you keep going it only gets worse, but if it hurts, you can keep going through that. The challenge is, it’s not always easy to tell the difference when you’re a newbie – you have to listen to your body and learn from experience about the difference between good and bad pain – it’s the same thing in the gym.

Yeah, I’ve heard you say similar things in the past, but talking about a different topic. Were there days when you got bored? Or were there days when things were so difficult you wanted to quit?

Yeah, both. Not many people asked me if I got bored. A lot of people asked me if I got lonely and no, I never felt lonely, but bored definitely. It’s an amazing adventure with amazing scenery, but it’s a long, long time to be out there with long, long days and there are some stretches that look the same for a long time and that can get boring. There are some sections like the burn zones that are not only boring, they can be a bit depressing and you just want to get through them.

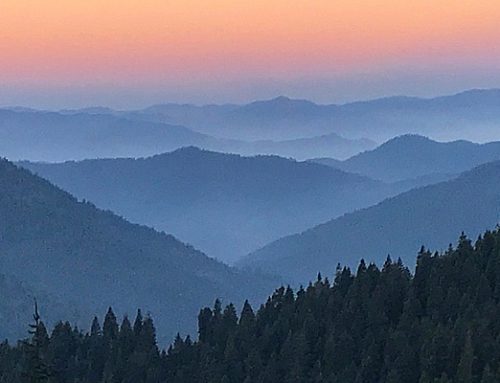

But the great thing about the PCT is that the scenery changes so often – you pass you through all kinds of different terrain from the desert to the high Sierra to volcanoes to rain forests, so the boredom never lasts for long. I always loved getting over a pass, or hitting that spot that was over the horizon and then seeing a completely new part of the trail open up in front of me, that was one of my favorite things about the PCT – seeing a new section for the first time. You can’t be bored for long on the PCT.

Reaching the top of a mountain pass was always a great moment, not only because you made it to the top, but also because a new vista opened up on the other side

Was it difficult? Yeah it was difficult. The PCT was the hardest thing I’ve ever done and there were more times I wanted to quit than I can remember. In the early part, I don’t remember having any serious thoughts about quitting the whole hike, but I constantly wanted to quit hiking early and crash for the day. It was later on, around mile 1000 that I had serious thoughts about quitting the whole trail. I was in shape to hike more miles, I could do 25 miles, but it never got easier and there were moments I wasn’t enjoying myself anymore.

I wasn’t sure why until I started to think about it and ask around on some of the social media groups and I found out there’s this thing called the post-Sierra blues, and I believe it’s real and it happens because the high point of the trail – literally and figuratively – is over and behind you – and for a lot of people, Northern California is not the most exciting part of the trail.

Plus the other thing that happens is you start doing some mileage math and you realize it took so long and was so hard to hit that 1000 miles milestone, but you still have 1600 to go – and that can be demoralizing – so a lot of people bail out at that spot – it’s around Tahoe. I pushed through it and when I got to the half way mark, around 1325 miles, I think that was a motivator to keep going because I was thinking that from this point forward, the miles I have to go are less than the miles I hiked.

That is just an incredible number of miles, it’s difficult to comprehend. So what did you learn about yourself, physically, mentally, or in other ways?

I learned a lot of things, about myself, stuff you can apply to life in general, about setting goals – there’s so many things I could probably write a book about it. What the trail does is it teaches you a lot of lessons.

I think probably the three biggest lessons I learned were one, don’t quit, two, set massive goals and as long as you break them into little goals all the way down to tiny daily action steps, there’s no goal too big, and three that it’s okay if you’re slow – slow and steady still gets you there.

That was a big one for me because I was slow. If you counted the stops for food and water, I only covered about 2 miles per hour per day. And for anyone who walks, even just around the neighborhood or around the city, you know that’s a really slow pace and that 3 miles per hour is an average walk and 4 miles per hour is a really brisk walk. But with a pack on and with all the elevation and the terrain I was on and with the rest breaks factored in that’s the pace that I covered.

But that’s still 20 miles in 10 hours, or 26 miles in 13 hours – a marathon a day – I just had to keep going a little longer after everyone else stopped. They were already in camp, roasting marshmallows, and had the fire going and I wasn’t even there yet. So I was a tortoise, but I usually caught up with the hares at the end..

On the Pacific Crest Trail, I found out that it’s okay to be a turtle… slow and steady still gets you there

Well those are great tips for everyone and you have said these things before in a different context – don’t quit, set big goals and progress not perfection – we talk about these things all the time at the Burn the Fat Inner Circle. Can you pinpoint to a single moment, the most difficult physical challenge, and the most difficult mental challenge you faced?

It’s hard to pinpoint a single moment, but there were two places in general that were incredibly challenging.

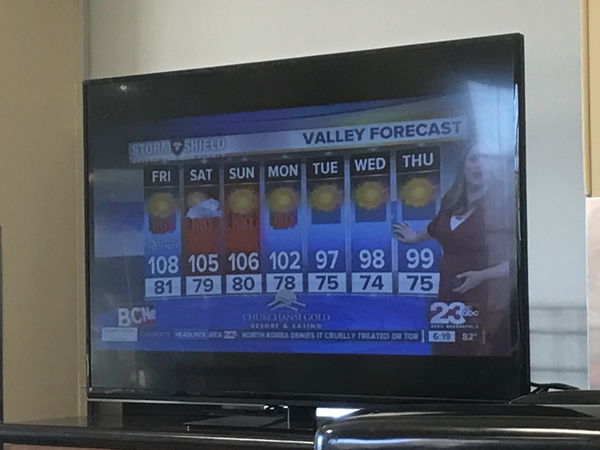

One was handling the heat in the desert. It was mostly in the upper 80’s to upper 90’s during the day, but 2017 was such a year of extremes. When I hit the section from Agua Dulce California to Hikertown, and then to Tehachapi, that’s when the triple digits hit and a lot of people quit then.

When I was in town resupplying my food I stayed in a motel and the TV was on and I saw the heat was the top story on the news. It hit 105 on trail and I heard it was 111 in nearby towns like Bakersfield which is not far West of the trail. People were being warned not even to go outside.

After you suffer through it a few times, you learn your lesson and what you do is start early in the morning, then sit out the day – take a nap if you can in the shade or if there’s shelter, get indoors – basically take a siesta during the day. And then what we did was put on a headlamp and hike at night in the dark – it was the best way to beat the heat. But it was so hot all the time, finding water and staying hydrated was a huge challenge for the whole desert section.

The funniest part of this weather report was when the newslady said there was a cooling trend coming up later in the week… you know it’s been hot when 97-99 is “cool”

The other big challenge was crossing the Sierra– that’s about 300 miles and it goes through extremely remote mountains and snow. It’s the most beautiful part of the trail, but it’s really tough to get through even in a normal year, and in 2017, the high snow year only made it harder.

They call it the high Sierra because you don’t drop back down under 7500 to 8000 feet. So you’re already at a elevation, almost like a plateau, and once you’re up there, the entire Sierra mountains are a series of even higher mountain passes – there are at least 10 passes over 10,000 feet.

And so every day we had to climb over a mountain pass and a couple times, two passes in a day. You would start around 8000 feet or so and climb up to 11,000, 12,000, even 13,000 feet, and then back down. The higher up you went, the more you felt the thin air and it’s a lot harder to breathe especially on the uphills.

The combination of elevation, going through the snow, scrambling over rocks, and fording the creeks made it really hard. It was always a slog it and tested you mentally as much as physically.

Glen Pass, at 11,926 feet was still snow covered in mid July, which made for slow going

This was such a larger-than-life experience, it must have led to personal growth and change. Can you share some of the ways you’ve changed as a person through your experience?

I don’t know if I changed as a person, I consider myself still me, but I would definitely call it a learning experience and a growth experience. Mainly I think I became more of what I already was and I learned to appreciate certain things more.

Like I already had appreciation for the wilderness, and I love the National Parks and I love going out and hiking on scenic trails and now that appreciation is bigger than ever.

And I’m on the introvert side, so I always appreciated solitude and silence before, and now I appreciate that even more.

I appreciated freedom before, and now I appreciate that more than anything.

And people. I appreciated people before, but on the trail, there is this incredible trail community, and all the times trail angels would give us rides into town from a remote trailhead in the mountains, or they stocked up water caches in the middle of the desert, or they brought us food and cold drinks on the trail, I appreciate more than ever how kind and how generous people can be, even to complete strangers.

One thing you’ll hear from almost every thru hiker is appreciating simplicity or a simple life more. I haven’t gone minimalist and I’m not anti-materialist, but after the PCT, you can’t help appreciate more than ever that you can be happy and have a peak experience without a lot of stuff. And if you lighten the load you’re carrying and get rid of clutter it can feel great and feel very freeing.

Definitely I got more physically tough, mentally tough, and I’ve grown more enduring. And again, that’s one of the biggest lessons the PCT taught me – don’t quit. I think I was already a persistent person, but never at the level it took to keep going so far on the PCT through so much. From that, I don’t think, for the rest of my life I’ll ever give up easily on any goal.

The best thing you will ever do in your life is have the courage to set huge goals, then go after them one day at a time, and never, ever give up!

Something you were just talking about a minute ago, and I did notice in your Instagram posts, is that it seems like the thru-hiking community is really tight-knit and people really look out for each other, and I wonder if you brought that attitude home with you and how you apply it to your life now?

Well, you know this because we have such a strong health and fitness community online, that I already appreciated and promoted as much as possible the idea of how important it is to have a support system. I mean, granted I hiked most of the trail alone, but you’re not alone on the trail. When you arrive at a campground, there’s other hikers there, when you arrive in a trail town, there’s other hikers there, and yeah, it’s very close knit.

There’s also this incredible rapport because you’re all doing something so unique and there’s so few people doing it, that when you recognize someone is like you, there’s an instant connection and there’s an instant respect and incredible support. Whether you have an injury and people say take a rest, but get back on, or if you feel like quitting, there’s people supporting you and saying keep going.

And the trail angels were the most amazing thing. They call these people trail angels because they’re volunteers who on own their own accord, go out to sometimes very remote locations, they may drive up in a four wheel drive truck or SUV, and in they bring coolers filled with cold drinks and food to the trail head.

And there you are after hiking 25 miles on a hot day, and you’re utterly exhausted and you run into these people who say, “Hey are you a thru hiker? You want a cold soda?” And the feeling you get from that is incredible, and I think the trail angels get an incredible feeling too seeing how much they helped someone. A lot of them are trying to give back. They may have hiked the trail the year before and they wanted to come back and give back to the community.

It’s 100 degrees, you’re exhausted, overheated and dehydrated, and suddenly, in the middle of the desert, you see a van, you’re greeted by a friendly couple, and they ask if you want a Coke and some watermelon… That’s “trail magic!”

It’s incredible. We have a great online fitness community at the Burn the Fat Inner Circle and so I know that anybody who has any big goal whether it’s losing fat and getting in shape or some kind of adventure like doing a thru hike, if they get involved in a tight-knit community, they’re going to do better and be less likely to quit.

Will you become a trail angel?

I will. Even if I don’t go back to California to do it, the Appalachian train is only an hour or hour and a half from me in New Jersey, and I did a lot of my training hikes on the AT, so I could easily go out to the trailheads and be a trail angel. Who knows, maybe out in California too, but either way, I’d really like to do it. I would love to pay it forward.

Coming up in part 3, Tom answers:

- What mistakes did you make on your thu-hike?

- Did you get post-hike depression?

- Did you form any bad eating habits on the trail?

- How did you transition back into normal eating?

- How have your metabolism and lean body changed after the hike?

- Is muscle memory really working?

- And much more. Click here for part 3

The high Sierra, seen from Mount Whitney trail – it’s a side trip off the PCT or you can backpack to the summit of Whitney from the portal in one or two days… put it on your bucket list – you won’t regret it!

Leave A Comment