Hi everyone, it’s Katherine Wilson here. I’m the Burn the Fat Challenge director at burnthefatinnercircle.com. I’m super excited because I have a special guest with me – it’s none other than Tom Venuto himself. For our readers and listeners here, Tom needs no introduction, but here’s the short version:

Tom is the author of two books, Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle and the Body Fat Solution, and he’s the founder of Burn the Fat Inner Circle online fitness community, a natural bodybuilder for over 30 years and now, he’s also a long-distance hiker. Tom, thank you so much for taking the time for this interview today

This last summer, you went on an exciting adventure, something that would be considered a bucket list item for many people. Tell us what you did, and your motivation for taking it on.

This last summer, you went on an exciting adventure, something that would be considered a bucket list item for many people. Tell us what you did, and your motivation for taking it on.

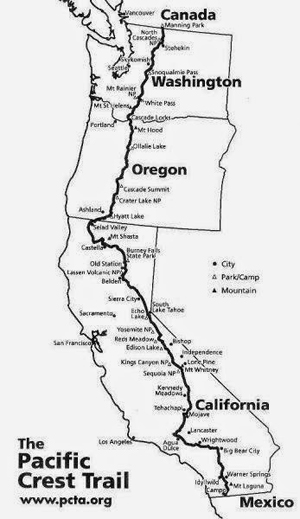

From May to September, I hiked the Pacific Crest Trail, or we call it the PCT for short, and it’s a 2650-mile national scenic trail that runs from the Mexican border all the way to Canada. It starts in the desert, and it winds all way through California, Oregon and Washington. It goes through 7 national parks, including Yosemite, 25 national forests, 48 federal wilderness areas, and it goes up and over 57 mountain passes.

The highest point is Forester Pass in the Sierra Nevada at an elevation of 13,100 feet, and you can take the side trip to Mount Whitney too which is the tallest in the contiguous United States at 14,500 feet.

For people with fitbits – that’s about 6 million steps, with 490,000 feet of elevation gain and loss. The trail is almost impassable in the winter so there’s a limited time window you can do it. Most people start hiking northbound in April or early May and need to finish before new snow flies in October in the north Washington Cascades.

It takes most people about 5 months, and that whole time you sleep in a little tent and you carry everything you need to survive in a backpack that weighs about 20 to 35 pounds, total, if you count the food and water.

Why did I do it? Well, it is one heck of an adventure, and that’s the big reason I wanted to do it – I wanted an adventure, and I wanted to experience the kind of freedom you can only get from being out there on the trail on your feet for months.

I also wanted a physical challenge – but something different than I’d ever done before. A lot of my friends have told me I should make a comeback to bodybuilding competition, but I’ve already done that almost 30 times. Did that, done that been there. So I wanted a new physical challenge completely out of my comfort zone; something that would test me and let me see what I’m made of.

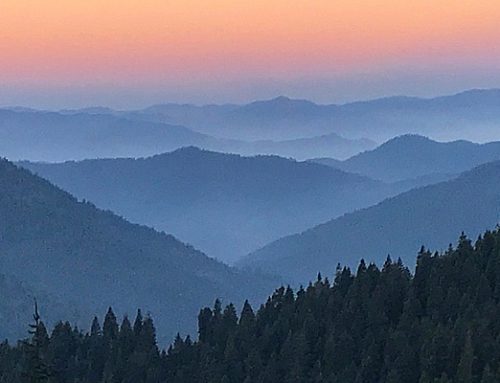

And last but not least, of course, the other reason I wanted to do this is to see the scenery. The PCT runs through some of the most beautiful wilderness not only in North America, but in the whole world. The Sierra Nevada mountains, especially, are spectacular, it’s like our own Swiss Alps right here in the USA.

Thousand Island Lake and Banner Peak, Ansel Adams Wilderness

Breathtaking Aloha Lake in the Northern Sierra, Near Lake Tahoe

You kept an extensive photo journal, so if people want to see all the cool, interesting and amazing photos, how can they find that?

That’s on Instagram at www.instagram.com/meathead hikes

What did a typical day look like on trail?

In a nutshell, a typical day on the PCT is walking all day. You wake up in the morning in your tent, usually before sunrise. You pack up your sleeping bag, tent, food and other gear and stuff it all into your backpack. You eat breakfast, toss the pack on your back and start walking.

You walk through the heat of the day, stop a few times to take a break and eat, and you stop to find water. When the sun starts going down, you look for a good campsite, pitch your tent, jump in your warm sleeping bag (because it’s cold at night even in the desert), and then you do it all over again.

For me it was about 20-23 miles a day of walking in the desert section, about 15 to 19 miles a day through the snow in the Sierra, and about 25-30 miles a day in Northern California where the terrain was a little easier. I did at least 20 miles a day in the Washington Cascades. I didn’t hike Oregon or finish Southern Washington because of wildfires.

Campsite with a view, Kings Canyon National Park

How often did you take a break? That’s a lot of miles in a day

I actually didn’t take that many breaks during the day. I mostly only stopped when I had to eat and I was eating a meal I had to prepare – I had to add water to it, or I had to eat it out of a bowl. Mostly during the day, I only stopped long enough to eat my meal.

I also took longer breaks from the trail when I got close to a town and I stopped to resupply my food which was about every 4 to 7 days. If I was close to a major town and I had a cell phone signal I could call a ride – I could uber – otherwise, I had to hitchhike, believe it or not, unless I lucked out and a trail angel or a day hiker offered me a ride. Even if town was only 7 or 8 miles away, you’re simply not going to walk that road into town after hiking 20 miles.

When I got into town, I would restock my food supply, have a nice restaurant meal or three, and usually I would get a motel and stay overnight and go back and hit the trail the next day. Every once in a while I would stay over two nights and we would call that a zero day because I would have an entire day with no miles hiked.

Not to be indelicate, but you were on the trail for 3, 5, 7 days at a time. Was it ever a challenge to manage your personal hygiene?

Oh yeah, it’s a challenge and everyone laughs about it – the “stinky hiker” is always a subject of conversation. You could jump into a creek or a lake, although believe it or not, it’s a bit controversial because you’re covered with bug spray and sunscreen, and the really environmental people question whether that follows leave no trace principles, especially getting soap in the creeks, which is really frowned on. But you just deal with it– you get really dirty and then when you get into town, the shower feels pretty darn good.

So the people who pick up hitchhikers know this?

Yeah, exactly. We got picked up once, and as we got into the car she said, “Oh, you guys are ripe!” But they’re used to it, and they’re not subtle about letting us know – they’ll roll down the windows, but it depends on the person, some people stink more than others.

To put it into perspective for people who have a pedometer, did you know what your average day would be for a step count?

It was probably about 55,000 to 60,000 steps per day average in the beginning and it would have measured about 70,000 to 75,000 later when I increased my mileage in Northern California, if I hadn’t lost my pedometer. Actually, I didn’t lose it, I accidentally killed it.

We had to ford a lot of creeks in the mountains and I had a Fitbit one in my pants pocket, and a lot of creeks are just ankle or knee deep, but every so often I crossed a creek that was mid-thigh or even waist deep and I kept forgetting that I had the Fitbit in my pocket, and it didn’t take too kindly to getting soaked over and over again so it died and I never replaced it, but when I did have the Fitbit for the first half of the hike, that’s what the steps came out to.

What FitBit stats look like after day hiking Mount Whitney, 22 miles round trip (27 total for day), 6000 feet elevation gain and loss

Wow, that’s a lot of steps. So did that lead to any injuries or other physical issues?

The main thing for me was foot pain, and it was so bad in the first three or four hundred miles, there were times I thought I’d have to get off the trail to recuperate or even give up. I think almost every thru-hiker feels this to some degree. It wasn’t an injury per se, it’s just how your feet feel after 20 to 25 miles. They even have a name for it – they call it hiker’s hobble. At the end of the day, you can recognize the thru-hikers even if they don’t have their pack on because they’re limping and walking funny.

But I think I suffered from this worse than a lot of people. At the end of almost every day, the bottom of my feet felt like they’d been whacked by a sledgehammer. If you imagine that the bones on the bottom of your feet were all bruised but you had to keep walking on them, that’s what it felt like.

On top of that, I had heel pain, which I never had diagnosed but it was almost for sure plantar fasciitis, maybe Achilles tendonitis because I had the classic symptoms. Some mornings I could barely walk, but then after 5 to 10 minutes, the tendon would loosen up and the pain in the heel would subside a bit. It was the worst uphill. When I was hiking up Mount Baden Powell – it’s a big 4 mile climb up to the summit – I remember that day the pain was the worst it had been – it was a sharp, stabbing in my heel and I was limping and I thought I might be finished right there before even hitting 400 miles.

But the pain would come and go, it was never constant, so I kept telling myself, “Keep hiking, it will go away again.” And it did. It was challenge through the whole hike, but it did get better over time when my feet and legs got stronger.

The view from the top of Mt Baden-Powell was glorious, but the hike up was excruciating with stabbing heel pain from plantar fascitis

Was it just improving your foot gear, or working through it? How did you do that?

The only thing I tried to do to fix it was I did stretch – it was just a calf stretch for the calf muscle and the Achilles, and I did that fairly religiously early in the hike. I did experiment with different shoes and some shoes definitely made a difference. I did best with maximum cushion shoes like Hokas. I know there’s been a trend for minimalist footwear, but that’s not so popular on thru hikes because you hike so many miles, so many days in a row, most people need cushioning. For me, it helped both issues – it helped general foot pain and it helped the plantar fasciitis as well.

That plantar fasciitis is excruciating, so kudos for you for pushing through that. Especially early in your hike, some of those water sources looked pretty sketchy. Did you ever get sick from bad water or food?

There were some sketchy water sources. There was one cistern with a dead rat in it. There was a creek full of oily reddish-brown mud. And there was a spring that was contaminated with Uranium – I passed on all those. But sometimes we had no choice. There was this one water trough with a sign that said, “For horse consumption only. Non-potable water.” It was green and there were clumps of algae floating around in it and some dirt in the bottom. There were dead bugs floating around, and live bugs too, swimming around.

It looked pretty gross, but it was a long dry stretch in the desert and everyone needed it, so I filtered it, and it wasn’t that bad. I filtered all the desert water and no, I never got sick, but there are all kinds of illnesses you can get from untreated water. Giardia is the major one, it’s an intestinal parasite, so on the trail you get warned to filter all the water even if it looks good.

On that note, there’s one thing I never told many people about until now, because I knew everyone would criticize me and say I was reckless – I didn’t filter any water in the Sierra. Why not? Nobody likes filtering water, it’s a pain the ass, so it saved me a ton of time and trouble. I also had a pet theory that up in those mountains of the high Sierra it was some of the purest water you could find anywhere – maybe more pure than my tap water in town.

I did realize that any water, anywhere on the trail can be contaminated, but I just considered it an experiment with a small amount of risk. I only did it in the Sierra and I was picky about the sources – I didn’t drink it if there were cows or horses around, and I didn’t drink from ponds, or pools of stagnant water. If I saw the water melting right out under the snow, or if I came to a creek where I saw the source was the mountain snow up above, I dipped right in and drank it unfiltered.

I did that for 300 miles through the whole Sierra section, at dozens, maybe even a hundred different water sources, and never got sick. But again, as a disclaimer, I would say try that at your own risk. I’ve heard giardiasis really sucks.

Water In The Desert On The PCT… Filtering Recommended!

That’s lucky, and pretty brave of you to do. What kind of equipment failures did you experience? And how did you resolve them, was it just duct tape or how did you do that.

Oh yeah, duct tape fixes everything! I had a few equipment failures. The first one was a tent pole broke. I temporarily fixed it with duct tape. But the pole kept cracking further up and eventually failed. I still had a working shelter, I just had the roof of the tent drooping on my face for a few days. When I got into Big Bear, it’s a major town, so I rented a car and drove down to the Rancho Cucamonga REI and picked up a new tent.

On the bright side, REI was great the way they honored their return policy and my new tent was replaced for free. Eventually I ended up with the same tent that broke because I liked it so much – it was a Big Agnes Copper Spur UL1 (HV) – that’s really popular on the PCT, I was just a lot more careful with my second one.

Another failure I had was my sleeping mat. A lot of hikers use a foam pad to sleep on, but I used an inflatable air mattress and mine blew out a baffle. It was a wide EXPED Synmat and I loved it. It was heavy and a pain to blow up every night, but it was a luxury compared to a foam pad. It lasted 900 miles, so I wasn’t disappointed with it, in fact, I replaced it with the newer model of the exact same pad when I got to Mammoth Lakes.

Later on my new air mattress got a pinhole leak in it so I had a rude awakening one night when I went from having a comfy soft bed to feeling hard ground and rocks underneath me. But that was easy to fix with a patch and glue. As long as you have a little repair kit, most of these things are just an inconvenience.

What was your scariest moment on trail?

There was more than one scary moment. Crossing snow chutes on the mountain passes was potentially dangerous in spots. Glen Pass was pretty sketchy and Mather Pass at 12,000 feet was one of the scariest. We had to walk across a steep mountain slope with a huge drop-off down below.

There was no trail, you couldn’t see rocks or dirt, it was all covered with snow, and we just put our feet into the footsteps in front of us. If you lost your footing and slipped, and you couldn’t self-arrest with your ice axe, you’d slide a thousand feet down at 50 miles an hour into the rocks or a frozen lake.

Glen Pass. If you slipped and fell here that would be bad. Ice axe and crampons strongly recommended!

But the creek crossings in the Sierra were the scariest. Everyone hiking in 2017 was concerned about getting through the snow, but crossing creeks and rivers was the most dangerous. There were two women who died in the creeks this year – one in Kings Canyon National Park and the other in Northern Yosemite – they were swept away and drowned.

There were some days I had to ford 6 or 7 creeks. Usually the water was freezing and that was uncomfortable, and it might have been moving fast so I could feel the current, but not a problem if it was below knee deep, and that’s what we tried to do – find places where the water was more shallow because it’s safer to cross. When the water gets mid or upper thigh deep, it’s easy for the current to knock you off your feet.

When I was in Kings Canyon National Park, the Sierra was on full meltdown in July – I never saw so much rushing whitewater in my life – it was like dozens of little Niagara Falls – there were creeks everywhere pouring off the mountains and flowing down into the bigger rivers and there were very few bridges – only places that were completely uncrossable had bridges, everywhere else we had to ford.

The rivers in the sierra were beautiful… but also potentially deadly

There was one spot just north of mile 800 where I came to a creek, I later found out it was called White Fork. It was running so fast, I wondered if I would have to turn around, or at least I thought about camping and trying in the morning because the snowmelt slows down overnight when it’s cold and there’s less melting water flowing into the creeks in the morning. But there were three hikers on the other side who already crossed so I figured, well, they did it, so I can do it do.

They all looked dead serious though. They yelled over from the far side and told me it was the toughest crossing they had done yet, and they pointed me to where they thought was easiest to cross. One guy stood on the far shore, held on to a tree and reached out his hand and the other two were about 10 yards downstream to “spot me” in case I lost it and got swept downstream. I could tell from their reactions this was no joke, and the consequences for falling in were really bad because this creek fed into a bigger river that was whitewater over rocks – if you got swept all the way down there, you’d probably have no chance.

But it was either turn around and hike for days back to the trailhead and go around that whole section, or forge on, so I waded in. I could feel how strong the current was right away, but at first, it was only knee deep and I planted my feet and trekking poles very carefully, one foot, one pole at a time, and I was okay. Then when I got to the other half of the creek I dropped in deeper, and then it was mid to upper thigh deep, which is always dangerous, and it was more than scary, it was terrifying.

I got almost to the other side and I had both poles planted and both feet planted, so I was steady, but I picked up my back foot to take one more step and the current took that leg and I almost lost it. I made a mad dash for the shore and I got out in one piece. I don’t think the adrenaline went down until I was in camp later that night. I haven’t stopped thinking about what kind of a risk that was ever since.

I’ll bet. I remember you posting on Instagram in that section where there was so much water and the trails were washed out – it was crazy. Did you have any embarrassing moments you could share?

I had one or two. I was slipping and falling all over the place in the snow, especially when my bear canister was full of food because once I started losing my balance, my pack was top heavy and toppled me over rest of the way.

I had the most epic falls, landing with my arms and legs twisted behind me in pretzels or doing a Charlie Brown like when the football was pulled out from underneath him – one leg goes up in the air, then the other leg goes out from under me, then airborne, then flat on my back. And plenty of times it was in front of someone. The good thing is that it was only an embarrassment, it was not a fall and slip down a mountain because if that happens it’s nothing to laugh about.

It’s part of hiking culture to use a nickname, or a trail name. What was yours and how did you earn it?

Well this is a funny story because the only nickname I ever had before the trail was meathead – and mainly my friends from the gym called me that – for lifters, it’s not meant as an insult, it’s like a term of endearment, sort of like “hiker trash” is a term of endearment, it’s not an insult. So I started an Instagram account with MeatheadHikes as the handle, and I thought maybe that would stick, and that would be my trailname, but I found out that it’s not traditional to give yourself a trail name, it’s something you’re given by other hikers after something happens on the trail to earn you that name, so I got a different trail name.

It was only the third day of my hike and I was in the desert in my tent, taking shelter from a windstorm, when a couple stopped by and said “sweet campsite!” because I had a spot in bushes totally protected from the wind. They introduced themselves as Rooster and Woodchuck – they already had trail names because they did the Appalachian Trail the year before. After we chatted, they said they were pressing on a few more miles. I didn’t see them again until a couple days later, and they came up behind and passed me, and I said, “I thought you were way ahead of me by now,” they said, “I thought you were behind us!” Then they flew past me.

The next day, they came up behind me, passed me again and said, “How’d you get ahead of us again, what are you doing, hiking at night? I said sometimes I hike at night, but mainly I’m just slow and steady. Then later that night, I saw them camped off the side of the trail, and I waved and I passed them and kept hiking into the night. Then a couple days later, I passed them, and then they passed me three times in one afternoon, and this time we all laughed and Woodchuck said, “We keep leapfrogging each other!”

Finally I caught up with them at a dirt road crossing where some trail angels had coolers of soda and Gatorade and watermelon and we were all hanging out there enjoying the cold drinks in the shade and talking about the hike and how funny it was they were a lot faster than me, but somehow I was keeping up with them. The best I could explain it was I said, “I start early, I don’t take a lot of breaks, I keep my breaks short, I haven’t taken any zero days yet, and I hike late, even in the night if I haven’t hit my miles yet. I’m a bit of a tortoise, but I just keep going.”

That’s when Rooster said, “Tortoise huh? Well that’s your trail name – Tortuga – it’s Spanish for Turtle.”

I picked up the trail name, Tortuga, early in the hike near the Anza Borrego Desert

That’s awesome – it’s a good thing they didn’t see you fall down a bunch of times or your trail name might have been different. You had to skip a large section of the trail due to fires. Can you tell us more about that?

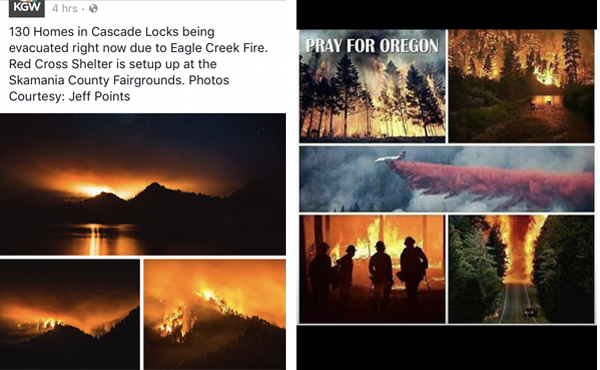

Yeah, the fires were one of the two biggest stories of the PCT in 2017 – they called it the year of fire and ice – ice because of the record snowfall in the Sierra – there was more snowpack up in those mountains than in the last 20 years – and it was also one of the worst years in history for wildfires.

The fire part is a bit of a long story because so much happened.

Really early in the hike I walked through a lot of burn zones from previous fires where the trees were dead and charred and black and I was shocked how many sections were burned. It was a real eye opener about how fire impacts the trail, but there was no smoke or flames at that point – I was seeing damage from old fires.

Then when I got near Mount San Jacinto I hit the first trail closure. It was from a fire a few years ago and the trail hadn’t re-opened yet. So some hikers would hitchhike or get a cab to the next town or trailhead, but the Pacific Crest Trail Association published an alternate route you could hike if you wanted to. If there’s a fire closure and there’s an official alternate, that essentially becomes the PCT.

If you walk around the closure instead of taking a car, you get to keep a continuous footpath, and that’s considered the holy grail thru hike. So in this case the alternate was part trail – not the PCT, a different trail – and part roads. Hikers usually hate road walking, but I walked the alternate to the next town, which was Idyllwild. I think the detour was less than 20 miles and it was no big deal to walk around.

Mount San Jacinto, in Southern California

What happened later was a lot worse.

When I was getting near Mount Shasta around mile 1200, that’s when I hit smoke. Mount Shasta is a massive 14,000 foot mountain, but on some days I could barely see it through the haze. When I got into the city of Mount Shasta for my food resupply, I looked up the fire report and got the bad news. There was a big fire north of Etna, California and the PCT was closed.

So I remembered San Jacinto and I looked for alternates, but this area was remote, and the fire was new and still burning, so the logistics of finding an alternate route on short notice were not looking good. The PCT Association and most other hikers said just hitch or get a car to the next town, Seiad Valley, to go around the fire.

But that was just the beginning. When I got to the Russian wilderness, I saw the plume of smoke from the fire near Etna summit. And when I got to the trailhead at the road, the Cal Fire trucks were parked there and one of the crew was guarding the trail to make sure no one went in – not that you would want to walk into an active fire zone, but there are hikers who would do anything not to lose their footpath.

That’s when I got the worst news– I saw the signs that said another fire broke out further north and I learned I wouldn’t even be able to hike to the last town in California, Seiad Valley or even cross the California-Oregon border. So between the two fires, a 100-mile section of PCT was closed and even if I knew how to find a detour route, I didn’t want to road walk 100 miles of road or get lost on alternate trails. So I got a ride up to Ashland, Oregon.

And that was a low point because that’s when I realized I wasn’t hiking the whole trail and I wasn’t going to have a continuous path of footsteps from Mexico to Canada.

Then when I got to Ashland, the whole area was smoky and when I checked the Oregon fire report, the PCT was closed at Crater Lake. There was an alternate route open, but a lot of people were skipping ahead because Crater Lake is a beautiful national park, but you couldn’t see anything through the smoke there either and some people said the smoke was so thick it burned their eyes and burned their lungs.

Then I found out there were even more fires in Oregon – Sisters wilderness – on fire. Mount Jefferson wilderness – on fire. Half the state was on fire. So a lot of hikers were saying to heck with it and ended up skipping most of Oregon, heading up near the Washington border, and that’s what I did. But then it still got worse.

Then I found out there were even more fires in Oregon – Sisters wilderness – on fire. Mount Jefferson wilderness – on fire. Half the state was on fire. So a lot of hikers were saying to heck with it and ended up skipping most of Oregon, heading up near the Washington border, and that’s what I did. But then it still got worse.

I took a bus to Portland where I met a friend and he was going to drive me to Cascade Locks where the PCT goes over the Bridge of the Gods – it’s a milestone for PCT hikers because it’s a state line crossing and it’s famous – even in movies like Wild. That same day I got to Portland, I got the news that the Columbia River gorge area was on fire, the Bridge of the Gods was closed, the PCT was closed and they were evacuating Cascade Locks.

That was pretty much the story of my hike. I don’t think I could have had worse timing. Fires kept popping up right in front of me. But I wasn’t ready to quit, I wanted to see how much more trail was open, so I figured I skip past that fire and hike north through Washington.

That was pretty much the story of my hike. I don’t think I could have had worse timing. Fires kept popping up right in front of me. But I wasn’t ready to quit, I wanted to see how much more trail was open, so I figured I skip past that fire and hike north through Washington.

But then I found out another fire broke out in southern Washington and there was a fire in the middle of Washington as well.

At that point the only choices left were to try hiking north and find detours around those fires, or my last resort was to go to Canada and start hiking south because Northern Washington had no fires – that I knew of. And that strategy made sense because you don’t want to get caught in the Washington Cascades if winter hits early – there were hikers that died up there because they got caught in storms – so flipping to Canada and heading south early in September was safer.

So I jumped up north and from the Seattle area I headed out to Hart’s Pass in the North Cascades, which is the last trailhead with a road to civilization before Canada, and when I got there, what do you think I saw? Smoke everywhere. There was another fire 10 miles from the PCT. The trail was still open, but the ranger said it could close at any time if the fire got closer so I bolted to Canada, tagged the Canadian border monument, got some pictures, and turned around and started hiking south.

I did, in fact, make it to Canada, just not the way I originally planned

This time, luckily, I caught a break, the smoke cleared and I got to enjoy North Cascades National Park and the Glacier Peak wilderness with clear skies – and that was one of the most beautiful sections of the trail next to the Sierra.

Ultimately I ended up hiking less than half of Washington southbound and I hit that 100-mile fire closure ahead of me. By then it was the second week of September, it had already snowed on me once, half of Oregon was still burning with hundreds of miles of trail closed and 100 miles of northern California was still burning with the trail still closed.

In between the fires, there was still 400 miles of open trail I could have hiked, but the logistics of jumping off the trail and back on to go around even more fires just wasn’t what I wanted, so that’s when I decided my hike was done.

I wish there had been no fires, but I did cover 1800 miles of the PCT and I feel like I got everything I wanted – it was definitely an adventure, and I got off the trail feeling great even though I didn’t do a full thru hike.

So the whole PCT is just over 2600 miles and you hiked about 1800 miles – that’s still a lot of miles. That’s huge. I can’t imagine that kind of physical accomplishment, that’s amazing.

Cutthroat Pass, North Cascade Mountains. Spectacular even through the smoky haze

Coming up in part 2, Tom answers:

- What kind of nutrition plan fuels 20 to 30 miles a day of hiking?

- How does body composition and weight change from burning 6000 calories a day

- Should you train in a special way to get in hiking shape before starting a long distance trek?

- Did you learn anything about your body or the human body over months of hiking?

- Do you have epiphanies or learn major lessons thru-hiking the PCT?

- What was the single most difficult challenge faced on the trail?

- And much more… Click here to read part 2

Tom ” Tortuga ” Venuto.

I saw the movie Wild, with Reese Witherspoon, and frankly am enthralled by your blog. Doing a hike like the one that you did, takes enormous courage, especially to do it by yourself.

Congratulations on this momentous accomplishment. You’ve got a lot of guts, and incredible inner strength to have done this hike. You ARE THE MAN TORTUGA!

Thanks! It was an adventure!